Credit to Goehring & Rozencwajg’s “The Problems with Copper Supply”, S&P Global’s “The Future of Copper“, @PauloMacro

With fears of a global recession rising due to the Fed hiking cycle and problems in China, industrial metals have done poorly. Copper has pulled back from recent highs of US$4.94 to US$3.69. While I see continued weakness as a possibility, I believe it’s an interesting time to start looking at certain Copper equities.

As is typical for every investment case with commodities, I’ll cover the demand and supply side, then discuss them in tandem and then take a look at equities.

Demand

According to S&P Global, demand for copper will increase from 25 million metric tons (mmt) annually in 2022 to 49 mmt by 2035 due to increasing energy transition and industrialization needs (Figure 1).

The demand is firstly driven by energy transition needs. It will require low-carbon power and automotive applications. These technologies, primarily EVs, and renewables, solar PV, and wind turbines in particular, are more copper-intensive. In addition, investments in the power grid are critical to support electrification. Overall, this will require an additional 13 mmt per year of copper by 2035.

Demand from nonenergy transition end markets—such as building construction, appliances, electrical equipment, and brass hardware and cell phones, will account for 11 mmt per year of copper by 2035. These happen because as countries industrialize, their copper consumption per capita increases both for manufacturing and consumer use (Figure 2).

Supply

Supply is likely to vastly disappoint. Supply growth comes from 3 sources: 1) lowering the cut-off for what constitutes “economic ore", 2) brownfield discoveries (new ore discovered near existing bodies) and 3) greenfield discoveries. All look dismal.

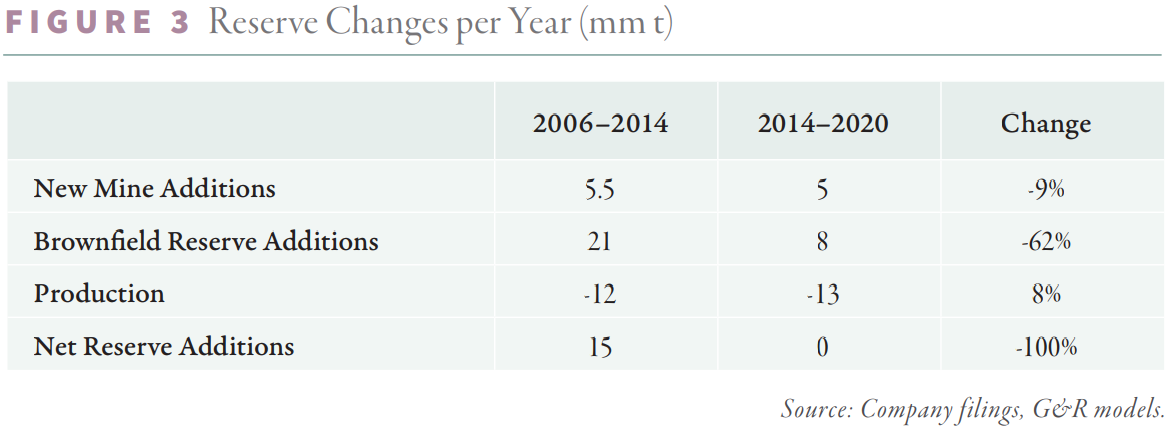

Most of the growth in copper reserves over the past 2 decades has not come from new discoveries, but from lowering the cut-off/reclassifying what was originally waste rock into economical ore. This can be done when copper prices rise, making subpar ore economical to mine, and was more pronounced from 2001-2014 than 2014-2020 (Figure 3 - brownfield reserve additions accounted for 80% of new reserves from 2001-2014). If lowering the cut-off grade were the major source of new reserves, one should expect to see the grade of new reserves added to fall. That is indeed what has happened, with new reserves in 2001 being 0.8%, and falling to 0.26% in 2012.

Going forward, this source of growth is likely not merely to decline, but exponentially so. 80% of copper is mined from copper porphyry. Copper porphyry has a log normal distribution (Figure 4). This means that most of the distribution is to the right of the peak. By 2014, the cut-off grade had likely been reduced from 0.4% to 0.25%, and from the curve, its evident that each equivalent reduction in cut-off, which requires exponentially increasing higher prices, also yields less tonnage (Figure 4 - lowering cut-off grade from 0.25% to 0.1% would yield 70% less than going from 0.4% to 0.25%). All additional ore is also of very poor quality and economical at very high prices.

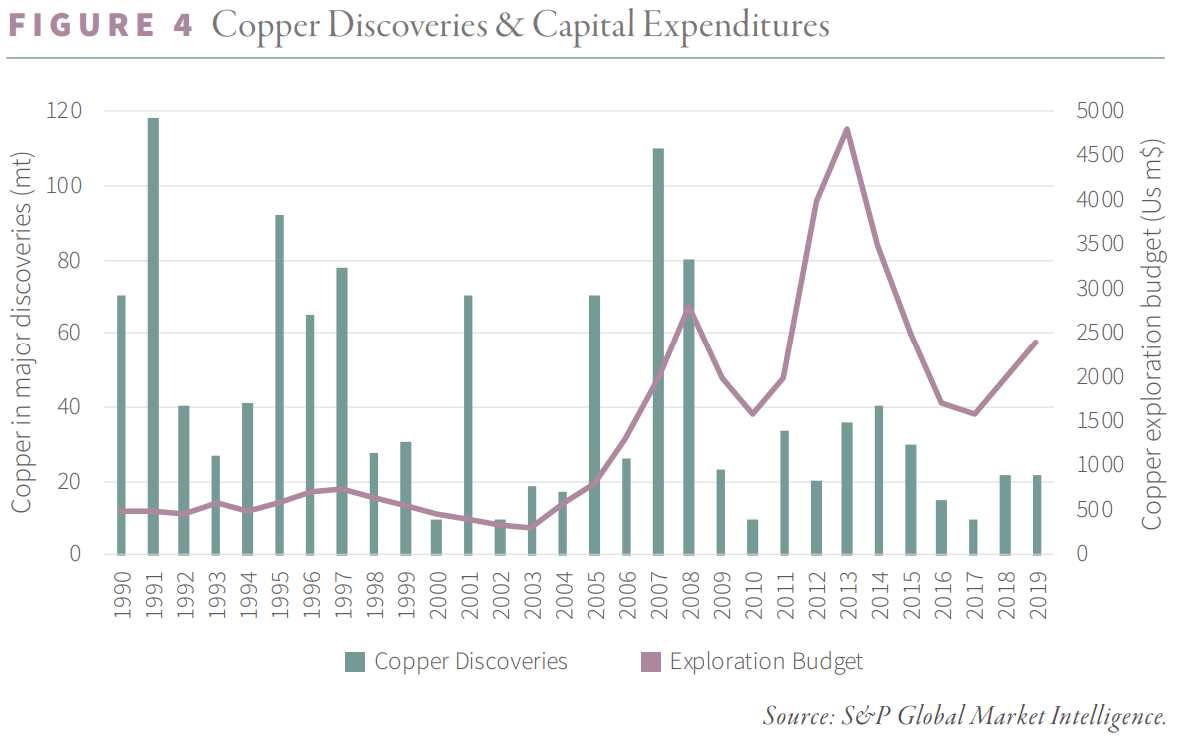

Both brownfield and greenfield discoveries have been falling and are increasingly difficult to find. S&P Global Market Intelligence estimates that new discoveries averaged nearly 50 mmt annually between 1990 and 2010. Since then, new discoveries have fallen by 80% to only 8 mmt per year. This has been partially due to a fall in exploration budgets as copper entered a bear market from 2012 (Figure 5). But it has also been due to a fall in exploration efficiency. Copper exploration budgets have increased more than three-fold from ~US$800M annually between 1990 and 2010 to US$2.5B annually since 2010, implying capital intensity surged 18-fold from US$17 to over US$300 per ton. The lower efficiency has been due to the diversion of exploration budgets towards more brownfield projects (expanding current deposits) rather than greenfield discoveries that have the potential to yield larger, fresh discoveries. Since the 1990s, the industry has halved its share of annual copper budgets devoted to grassroots exploration, with the 34.0% allocated in 2021 near the low of 32.2% set in 2009.

The lack of greenfield exploration has been due to many factors, which seem intractable. Firstly, there are long lead times. The National Mining Association estimates that it takes 7-10 years on average to obtain the permits necessary to bring a mine into operation in the US. The lead time is even longer starting from the moment of a deposit's discovery. The whole process can take 20 years. This is the case in the developed world, and in jurisdictions where this is not the case, there are usually tradeoffs (political instability, for example DRC). This discourages greenfield exploration. Secondly, there is increasing jurisdictional risk. Latin America, which accounts for 40% of global copper production, is increasingly hostile to mining companies. It is unlikely western companies will be exploring in China (8.5% of world production) or Russia (4.3% of world production).

The overall effect is that we are seeing less replacement (Figure 3 - in 24 analyzed copper mines by Gorozen, new mine additions + reserve additions only keep up with decline), and falling grades.

Synthesis

What is the combined effect of demand and supply? The S&P Global’s 2022 paper, “The future of Copper”, presents a “High Ambition” scenario where everything goes perfectly for supply. We maximize production from existing mines (Figure 6 - above maximum utilization rate from 1994-2020), which will bring primary mined supply to 37 mmt in 2035, with 10.4 mmt of recycling (Figure 7 - above our current maximum rate) helping bring total supply to 47.4 mmt (4.7% CAGR from today, ending at just under 49 mmt of projected demand). Their “Rocky Road” (less optimitic) scenario assumes a 3.2% per year CAGR in total supply until 2035, which results in a shortfall of 10 mmt.

Considering what was said above about demand and supply, both the “High Ambition” and “Rocky Road” scenarios are impossible. Between 2000 and 2020 mine supply plus scrap grew by only 2.5% per year (this includes a 2000-2011 bull market in Copper with the Chinese boom). At that growth rate, we would expect 35.3 mmt of total supply in 2035. And with lowering the cut-off grade no longer viable with already dismal grades, and near total drop-offs in new discoveries (Figure 8), we would expect growth to be even lower. And note that 35.3 mmt is not even enough to meet growth from non transition uses alone (36 mmt), which assumes zero additional growth in copper demand from the green transition (an impossible proposition).

What if there are improvements in recycling? Even so, while recycling efforts in advanced economies are expected to gather force over the next 25 years, the slow shift in the regional composition of demand away from these economies presents a challenge to lifting the global recycle rate in the long term. First, the recycling infrastructure in these emerging markets will remain less well developed, with scrap collection less efficient. However, second, and more important, much of the copper used in the emerging markets over the next 25 years will not have reached the end of its useful life. Even if scrap collection and processing were on par with the advanced economies, the supply of scrap will still be relatively scarce.

What if there are improvements to technological efficiency? Firstly, none of the green transition technologies are new and have already gone through extensive iterations. Further gains are likely to be limited. Secondly, copper will never be eliminated, and we see above that generous growth rates in total supply (2.5%) do not even allow us to meet demand considering zero growth from green transition needs.

What if there is substitution from other metals? Copper has unique recycling and conducting properties (closest substitute is Aluminum, which has 60% of the conductivity) and is unlikely to be substituted.

What is the state of the market now? Copper prices have decline temporarily, with a global slowdown, especially in China, which consumes half the world’s copper. And yet, despite the slowdown, the price is still very robust at US$3.69. Meanwhile, inventory levels are approaching critical levels (Figure 9), making the market extremely fragile (or anti fragile if you are an investor). While demand could continue to fall, most of the negative events have already happened and the worst may be over. If there are significantly undervalued equities, I am willing to start building positions. I don’t expect a sharp increase in price to happen imminently, as the copper thesis is a decade long one, but I believe (as seen later), that there are companies that are already attractive even at current copper prices.

Salazar Resources

Salazar Resources (TSX-V:SRL) has a market cap of C$15.5M and is trading at C$0.105 per share as of 8 Nov 2022. It is a prospect generator, which is to say that it explores and sells prospects (potential ore bodies) to other companies.

As of Jun 2022, company has C$2M in current assets (C$700K cash), C$26.8M in non current assets (C$1.4M property, plant and equipment, C$10.4M exploration and evaluation assets, C$14.9M investment in associated company - El Domo project discussed below). They have C$480K in accounts payable and accrued liabilities. The company’s burn rate was C$662K in 1H2021, and C$852K in 1H2022. Management fees are US$350K.

El Domo

The main asset of the company is it’s 25% carried interest (gets 25% of upside without any expense) in the high grade El Domo copper-gold project. It’s partner in the project in Adventus Mining, and the terms are that it will receive 5% of cash flow from the mine until Adventus is paid back, following which it will receive 25% of the proceeds.

The company concluded a feasibility study in 2021 on El Domo. The mineral resources are both open pit and underground, and can be considered separately:

Proven & Probable Mineral Reserves (open pit):

Proven: 3.1M tons at 2.50% Cu, 2.83 g/t Au, 41 g/t Ag, 2.30% Zn, 0.2% Pb

Probable: 3.3M tons at 1.39% Cu, 2.23 g/t Au, 50 g/t Ag, 2.67% Zn, 0.3% Pb

Underground Mineral Resources:

Indicated: 1.9M tons at 2.72% Cu, 1.37 g/t Au, 31 g/t Ag, 2.38% Zn, 0.14% Pb

Inferred: 0.8M tons at 2.31% Cu, 1.74 g/t Au, 29 g/t Ag, 2.68% Zn, 0.11% Pb

Total Measured & Indicated Mineral Resource (open pit & underground):

Measured: 3.2M tons at 2.61% Cu, 3.03 g/t Au, 45 g/t Ag, 2.50% Zn, 0.24% Pb

Indicated: 5.7M tons at 1.83% Cu, 1.98 g/t Au, 45 g/t Ag, 2.64% Zn, 0.24% Pb

M+I: 9M tons at 2.11% Cu, 2.36 g/t Au, 45 g/t Ag, 2.59% Zn, 0.24% Pb

Inferred: 1.1M tons at 1.72% Cu, 1.62 g/t Au, 32 g/t Ag, 2.18% Zn, 0.14% Pb

The company expects the revenue split to be 50% copper, 28% gold, 15% zinc and 2% silver (Figure 10).

Base case for open pit: Assuming prices of US$1,700/oz Au, US$23.00 /oz Ag, US$3.50 /lb Cu, US$0.95 /lb Pb and US$1.20 /lb Zn, the resource has an after tax NPV at 8% discount of US$259M, with after tax IRR of 32% and payback period of 2.6 years. The cumulative first 6 years of after tax cashflows (US$ M discounted) would be US$495M. The average annual payable production from years 1-9 are 11 kt Cu, 26 koz Au, 12 kt Zn, 488 koz Ag, 0.5 kt Pb, convertible to 23 kt CuEq (Copper equivalent). The copper equivalent AISC is US$1.26 per lb.

Underground estimate as of 19 Oct 2021: Using 19 Oct 2021 spot price of US$4.72 per lb Cu, and AISC of US$1.41 per lb, after tax NPV at 8% discount is estimated to be US$49M.

The project is fully financed with:

US$175.5 million upfront cash commitment from Wheaton in a streaming deal, and US$500k for local community development. Under the stream, Wheaton will buy 50% of gold production until 150k oz have been delivered, and then 33% of gold production for the life of mine. Wheaton will also buy 75% of silver production until 4.6M oz have been delivered, and then 50% for the life of mine.

US$45M of senior debt from Trafigura, and an additional US$10M in equity.

Experienced Ecuadorian and Peruvian firms have been contracted, and pre construction work has begun on site. The firm is still awaiting final permits for El Domo, expected to be delivered in 2022. It expects to begin first commercial production by 2024.

Meanwhile, the company is receiving advanced royalties of US$250K from El Domo.

Other projects

Salazar is also partnering with Adventus on Santiago and Pijili projects, retaining a 20% carried interest on those. Both project areas host copper-gold porphyry exploration targets, in conjunction with epithermal gold and silver veins. A Phase 1 drilling in 2021 identified porphyry targets. No work has been done in Santiago yet.

Salazar has 100% ownership (or option to acquire 100%) of 6 projects in Ecuador: Los Osos, Los Santos, Macara Mina, Ruminahui, El Potro and Columbia:

A Phase 1 drilling was completed in 2021 at Los Osos. It looks low grade, not particularly interesting.

Multiple Au-Cu targets were found and drilling is underway at Los Santos

Drill targets are being evaluated for Macara Mina

Drilling happened in 2021 at Ruminahui, but not promising

Au-Cu target was found and drilling will take place in 4Q2022 at El Potro

No work has been done at Columbia yet

Salazar also wholly owns a subsidiary, Andesdrill, which has 3 drill rigs, that can provide US$0.5M-1M in income. If needed, it can also use the drill rigs for their own exploration.

Share structure

There are current 154M shares in circulation, with 6.9M in options and 2.2M in warrants, for maximum dilution of 5.6%.

There is significant inside ownership from the Salazar Family and Directors/Insiders, at 34% (Figure 10)

Risks

Salazar is 100% Ecuador-focused. We spoke above about geopolitical risks in Latin American countries, and there are many risks here (country crisis, increasingly hostile politics). However, Salazar Resources has built good relationships with the government. In June 2022, the Ecuadorian government committed to an investment protection agreement for the El Domo project, which provides guarantees on security of title and investment, reduced tax burdens on both income taxes and the capital outflow taxes, guarantees on infrastructure development, among other items, which are customary features in similar agreements the government has established on other major Ecuadorian mining projects. This should provide some security.

Development risk is always present, but it will probably only delay the eventual production. The hired contractors are skilled, the project is high grade, and financed by experienced players like Trafigura and Wheaton (whose payoff also relies on successful production).

Exploration risk is always present, and so far, outside of El Domo, it’s too early to say if any of Salazar’s prospects will yield any fruit. But because the stock is undervalued, we are getting this upside for free.

Dilution risk is low. The advanced royalty payments and drill rig income more than cover than management fees. Having their own drill rigs also allows for exploration to happen with far lower costs. From Freddy Salazar, CEO and president: “I fully intend to find another deposit in Ecuador, and ideally have funding from El Domo to minimize dilution while drilling.”

Conclusion

I consider Salazar to be highly undervalued.

The drill rig income and advanced royalty from El Domo will be able to cover management fees.

It has a market cap of C$15.5M, with ~C$28M in net assets. This is with the assignment of an extremely conservative C$14.9M valuation to the El Domo project. The project (excluding underground, which is not yet fully explored) has an after tax NPV at 8% discount of US$259M assuming conservative copper prices of US$3.50 per lb (and likewise conservative assumptions for the other metals, all of which I consider to have bullish prospects going forward). If copper were to go to US$4.72 per lb, the equivalent NPV would be US$423M. While NPV accounts for financing costs and discounting, I am unsure if we can apply a flat 25% on the NPV of the whole project to yield the NPV for Salazar. But even applying 20%, the base case is a NPV of US$51.8M (C$70M as of 8 Nov 2022) for Salazar. Substituting this for the company’s own valuation of El Domo, we obtain ~C$83.1M in net assets, 5.36x the current market cap. And this is for a de-risked asset that is on track to commercial production by 2024, with strong partners and what seems to be smooth relations with the government. The upside if copper prices were to rise would be even greater, likely >10x.

I hold 140,000 shares of Salazar at average price C$0.12.

What a less risky name, larger cap name for copper that you like ? I am done playing with penny stocks.

Longer term s/d analysis is good but I think estimates for demand can still come down. China new housing is in the dumps and doesn't look to be changing anytime soon. Ditto for global real estate.